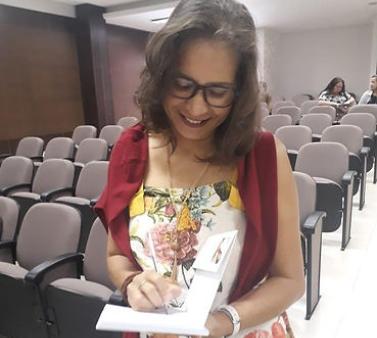

Obrillant Damus on Rennes 2's Villejean Campus

While at Rennes 2 University, Professor Damus presented ten lectures, took part in the Villages des Sciences, and discussed the prospects for future collaboration between Rennes 2 and Haitian universities. This is the first time that a teacher-researcher of Haitian origin has held the Americas Chair position.

Some of your conferences dealt with the complex relationship between Creole and French in Haiti. What can you tell us about the use of these two languages in this context?

Damus Bright: All Haitians speak Creole regardless of their level of education. Creole is the language of the illiterate, of the rural masses, but it is also the language of intellectuals... It was only in 1987 that Creole became an official language in Haiti, alongside French, which had been the only official language since 1804. Today, many official texts are written in French and Creole.

What is the language spoken on a daily basis in Haiti?

O. D. In everyday life, in the street, we express ourselves in Creole. If we want to make a good impression, in formal situations, we express ourselves in French. Generally speaking, the more educated one is, the better they will speak French. Haitian schools are practically bilingual. We teach in French, but nothing prevents a teacher from expressing themself in Creole. On the other hand, the teaching materials are in French. Not all students understand French in the same way. I teach at two universities, one private and the other public. In Quisqueya, I speak French, and students are typically able to provide good presentations in that language. This is not the case for students at Haiti State University.

You also gave presentations to schoolchildren at the Village des sciences organized on the Rennes 2 campus in October 2018... What are the topics you discussed with them?

O. D. Some had never heard of Haiti and they confused this Caribbean country with Tahiti. I explained to them that Haiti was a Latin American country, which had been colonized by several European countries, first by Spain, which enslaved the Amerindians. In Haiti, there were one million Amerindians when Christopher Columbus arrived. They disappeared completely in the colonial disaster because they were not able to resist the diseases transmitted by the new settlers. I also talked about the representation of the disease in Haiti: in France, we have a localizing perception of the disease. For example, syphilis is caused by a bacterium located in the brain. With medication, we can eradicate it. In Haiti, the disease is rooted in a labyrinthine network of representations. When someone is sick, it is the whole person who is sick, the whole family, the whole village. The cause of the disease is not singular, it is multiple. People tend to wonder if maybe it was a spirit that provoked it... I myself am of humble origins. When I was younger and sick, we first went to see a traditional practitioner, a specialist in Creole medicine, who made a divinatory diagnosis to determine the origins of the disease. If we didn't get better, we would go to a doctor. The trajectory of healthcare in Haiti is complex.

Can you tell us more about your research topics more specifically?

O. D. They are numerous. I have worked on issues surrounding rape in Haiti, cancer, breastfeeding, local knowledge systems, disability, Creole medicine, the relationship between Creole and French, ontological vulnerability... Since 2006, I have been particularly interested in traditional childbirth, which is carried out by mothers whose professional practice dates back to the colonial era. This practice constitutes an intangible cultural heritage of humanity. My work on traditional childbirth was crowned by UNESCO in 2016.

More on Obrillant Damus:

Obrillant Damus also holds a Master's Degree in Educational Sciences (Lifelong Learning specialty, in 2008 he received the Master's in Humanities and Social Sciences from Cancéropôle Île-de-France), a Master in language sciences (specialized lexicography and discourse in Francophonie) and a doctorate in socio-anthropology of health. He is the author of several works including "Homo vulnerabilis. Rethinking the Human Condition "(2016)," Humanist Solidarities "(2016)," Las prácticas profesionales de las matronas haitianas: between salud, biodiversidad y espiritualidad "(2017) in Knowing our Lands and Resources Indigenous and Local Knowledge of Biodiversity Ecosystem Services in the Americas, UNESCO, Paris.