Pictured: Paloma Fernandez Sobrino

© Antoine Chaudet

As I understand it, both the Fusée de détresse (Distress Rocket) and the Encyclopédie des migrants (Encyclopedia of Migrants) are very intertwined projects. Could you tell us about your first project - the Encyclopedia and how it developed?

Paloma Fernandez Sobrino (PFS): Yes, the Encyclopédie des migrants is a European artistic and scientific project that I first began with the organization L’Age de la Tortue located in the southern Blosne district of Rennes in 2014. We began by asking persons who had migrated, if they could provide us with personal testimony on their experiences of migrations, and to do so specifically in the form of a letter written to a loved one back home. These intimate accounts speak to us of what distance (from one’s home, culture and a larger familiar context) produces in an individual.

Initially, the scope of the project was mainly the residents of the Blosne neighborhood. Then, after a lot of reflection and discussion with my collaborators, colleagues as well as the project participants, we decided to expand it to eight cities of the Atlantic coast, from Brest to Gibraltar, through 4 different countries: France, Spain, Portugal and the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. We created a citizens' think tank, or reflection group, with residents of those neighborhoods that were involved, and they came from all walks of life, and included people of all ages and nationalities. We decided on everything in a participatory fashion, the ethical structure of the project, how we organized the testimonies, how we integrated the articles of the researchers, etc. We faced a lot of hurdles and challenges, logistically speaking, in establishing a network of municipalities, local organizations and photographers with whom we could work to achieve the final project vision - which is a collection of 400 migrant letters, photographs and scientific articles.

In terms of the scientific articles, how did you organize the work with the researchers?

Gudrun Ledegen (GL): Initially, the project was also co-led by Thierry Bulot, a Rennes 2 teacher-researcher and member of PREFICS research unit at that time, who was an internationally renowned specialist in urban sociolinguistics. Paloma and Thierry, along with a graduate student (Thomas VETIER), had already begun the large task of gathering scientific texts to be included in the Encyclopedia. The texts are based on the letters, and present sociological, sociolinguistic, ethnographic analyses. When Thierry became sick, that’s when I got involved in the project. So together, we continued this work with researchers in the humanities and social sciences who brought another perspective to the question of migration.

PFS: Yes, we took on a rather unconventional approach in how we worked with the other researchers. That is to say, we didn't give them a corpus in advance so that they could do a typical kind of analysis and research, but instead they accompanied us in our exploration of our main concepts. The research texts that are inside the Encyclopedia take the viewpoint of the construction of Europe from the perspective of migration. So we have urban sociolinguists, of course, since that was the scientific direction of PREFICS at that time, as well as anthropologists and sociologists, historians and others. And each person worked from the perspective of their own research and found how that echoed the work that was being done in the framework of our project.

Pictured: Gudrun Ledegen

© Bertrand Cousseau

GL: In the end, we have included articles from 16 researchers, which are placed not in a separate section of the work, but rather are integrated within and throughout in the same way as the other project participants. And this is a symbolically important point. We didn’t take the perspective that the researchers and their contributions would hierarchically structure the rest of the contributions. Instead, they are included in an alphabetical order exactly as was done for each letter-writer.

So, the project ran from 2014 and 2017, and now the general public can access the Encyclopedia in several different places?

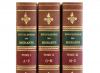

PFS: Yes, we compiled the letters, scientific texts and commissioned photographs to accompany the letters into an encyclopedic work of 3 volumes. The print version is a beautiful leather-bound artist's book which was published in 8 copies. One copy has been deposited in each of the 8 partner cities. In Rennes, it’s available at the Bibliothèque des Champs Libres. It’s also in the national Musée de l'histoire de l'immigration in Paris.

GL: I would also advise people to have a look at the website which is spectacularly done. There were 74 different languages used in the Encyclopedia of Migrants, and we kept all the original copies in these native languages. Afterwards, we translated everything into French, English, Spanish and Portuguese, which are the official languages of the four partner countries of the project of the Encyclopedia. We kept the facsimiles of all these handwritten letters and they are also available online as well as the translations and photographs. You can search for letters or other contributions by country of birth, country of residence, language, or you can even choose to have the platform select a contribution at random. The amount of information contained within it is really breathtaking, and thankfully, the overall project has had a lot of success. It's recognized as a great example of what a European project can achieve. It’s also been very well received by several French institutions and others.

And what led you to create this second production, Fusée de détresse, which also involves the letters?

PFS: Well, in fact, the Encyclopédie des Migrants was first designed to be a project that allowed us to put on the performances of Fusée de Détresse. I am a director and my background is in the performing arts, dance and theatre specifically. L’Age de la Tortue is a very multidisciplinary, hybrid organization, but my base comes from dance and the theater. I had therefore imagined the Encyclopedia as a sort of source of texts for the performance but it became immense in comparison to the performance elements. And, in the end, I’m happy about the way it turned out, there’s so much insight to be gained from this work.

The idea was to mount creations of live art in the form of performances based on the corpus of the Encyclopedia of the Migrants. So, we formed city partnerships with six European cities from Rome to Istanbul, and we set up artistic productions with coordinators, photographers, directors, professionals, amateurs, migrant people or non-migrant people, all mixed together. And the guidelines we established for these productions specified that everyone had one week to make a creation in situ and the participants needed to be people who did not know each other beforehand. So the director had 5 days to create a show that was going to be performed the following day. On day 6, the show was played in a festival or in some other common European context. On day 7, we held seminars where we all met and we exchanged with regard to the returns of this collective experience.

GL: Our first performance production took place in Belgium. We brought in a local Belgian researcher in sociology and a theatre director, Frédérique Lecomte, a musician Piet Maris and migrant actors, professionnals and amateurs: we went four times into town, in very different places, while having MP3’s in our ears where we heard the slowly read letter. Then we sat on stools in front of other people and repeated the letters in the languages we master, often under an umbrella. I read quite a bit in Dutch and English and, since Brussels is a very multilingual city, people were extremely interested in what we were doing. Officially, there are 70 to 90 percent of French speakers in this bilingual capital city, so proposing Dutch was really politically important. It was a really touching moment.

I imagine it was also a very hectic experience as well. Did the different teams working on the project feel panicked with only a week to coordinate each time?

PFS: We definitely worked with a sense of urgency and throughout the coordination and production of each performance production. But at the same time, I wanted us to work with this immediate feeling of pressure, this notion of distress. We needed to ask: what can we do as artists, researchers and as citizens to help bring to the table the pressing questions surrounding the political and social situation of migrants in Europe today? And how do we motivate and involve more citizens, public decision-makers, and the media in this process as well? But yes, it was definitely a crazy experience that I don’t think any of us will ever forget.

We managed to overcome the numerous constraints that threatened to jeopardize the project, particularly during the heightened Covid period. For example, in Milan, one of the first regions to be seriously affected by Covid in Italy, we played with masks and gloves in the public space. We couldn't touch each other, we couldn't have coffee together, we couldn’t eat together. We also had difficulties in Istanbul, given the sensitive political context, we were worried about putting the researchers, students and the theatre troupe who participated in danger. So we took a lot of care to ensure that we were doing things in as safe a manner as possible. It was also pretty complicated to manage the last production we did in Rennes as well. There were Covid constraints, numerous institutional partners to take into account and technical changes that had to be made at the last minute. So there were clearly moments we were worried that we didn’t know how it would all come together.

So, Fusée de Détresse was for me one of the most difficult projects of my life, but it's certainly the one I'm most proud of, which might sound surprising. Even though the Encyclopedia was a project that was 100 times more difficult, the conditions we were dealing with while creating with Fusée de Détresse were really extremely difficult. But it's all the more worth it because we managed to accomplish it. It was really quite amazing that we did everything that was planned. I think it's one of the few European projects that are finished exactly as planned. We managed to stay on course in a somewhat miraculous way, but it was a balancing act. And, even in those difficult moments, we managed to keep the feeling that we were painting the same picture together.

GL: Scientifically, with our words, and artistically, with our talents, we shared in these acts of creation. Even if it can be complicated in practice to put together, we still managed to find a way to advance because we all have the same goal in mind. This was evident even from the beginning, even though we didn't all have the same terms, the same way of using them, etc., but then, at a certain point, we knew that what was important was that we had the same idea. It’s a really great example of what participatory research and artistic projects can be and it’s thrilling that it’s finally visible.